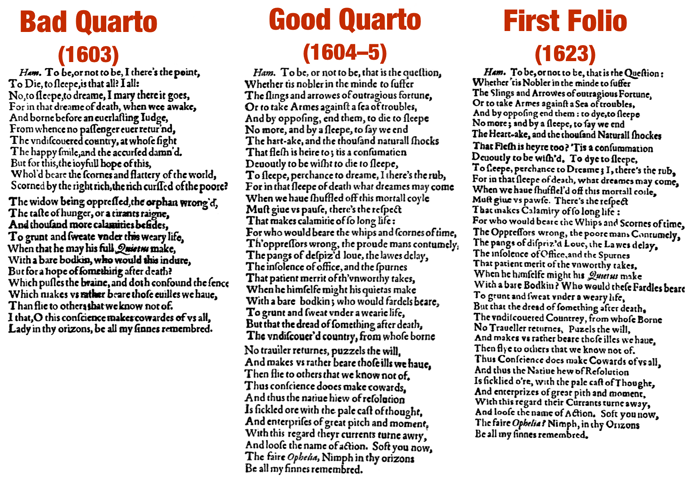

- Three drafts of ‘to be or not to be’. There’s probably a bunch more where that came from.*

First drafts are the raw materials of my industry. I get to read a lot of them. I love them. They are what they are; the first in (hopefully) a progression of ever more distinguished versions of a good story. Whether you are a complete novice or you have fully emerged from those difficult, uncertain times to the infinitely more difficult and uncertain times of being a hardened professional, first drafts never stop being appalling things.

I’m convinced there is not a person alive who writes a perfect first draft. A writer friend of mine called the first draft just a ‘vomit of ideas’. I’ve been known to call them ‘word pies’, such as a child might cobble together sloppy offerings from a puddle of mud. Others have been far more to the point and declared “the first draft of anything is shit”**

I know. Kind of takes the wind out of your chest, doesn’t it?

If you read any early drafts of Shakespeare’s plays, you’ll feel better about this, though. Recently I read a couple of beta versions of Hamlet’s soliloquy; you know, that old to be or not to be chestnut. Some versions of it are depicted above. The earlier versions certainly do lack star quality. See? Even Shakespeare had to redraft. And I’ll bet he wrote about twice as many versions of this text as we know about, scrunching up each one and landing them in the waste paper basket as he went, whilst muttering a stream of excellent Shakespearean curses.

So if we must be honest and admit that the first draft of everything we write will be an absolute shocker, what is the good of a first draft? A student of mine said she’d like to just skip to the second or third draft and save herself some embarrassment.

I needed to remind her (and myself) that first drafts are really useful disasters. If you allow the experience of the draft to unfold in all its dishevelled glory, you are permitting your mind the chance to disgorge on the topic at hand. So much of what you find on the paper at the end of this disgorgement will not make it to the final cut. But it will be useful to see what doesn’t work and what does.

Here are a few things that a first draft will almost certainly have going on.

1. Often the first draft will include far too much about a certain topic, or incorporate too many different topics. As we say in the theatre, a first draft will have more than one play in it. Reviewing your first draft, you will need to pick your best story out from the others that may be fighting with it for attention.

2. Often first drafts will be over-written. An old enemy of a good story is exposition; telling the emotions of a story instead of showing the emotions, or including great whacks of back story or insisting on long monologues to wring out the juice of the idea. Keep your eyes wide open for too many words and not enough change.

3. Often a first draft will contain dogma. As authors, we tend to have strong views on things. Thank the Lord! The topic of our stories come from a place of passion and rightly so. But the first draft is probably the only draft where it should be obvious where your feelings lie about the topic. Drafts after that need to fill in a broader picture, a broader understanding of other approaches to the topic, and a kind of non-partisan stance, allowing the audience or the reader to pick their sides. Susan Sontag says it so well:

“Obviously, I think of the writer of novels and stories and plays as a moral agent… This doesn’t entail moralizing in any direct or crude sense. Serious fiction writers think about moral problems practically. They tell stories. They narrate. They evoke our common humanity in narratives with which we can identify, even though the lives may be remote from our own. They stimulate our imagination. The stories they tell enlarge and complicate — and, therefore, improve — our sympathies. They educate our capacity for moral judgment.” —Susan Sontag

4. Often first drafts are shallow. Even if you have spent a lot of time on research or have actually lived the events of the story yourself, your first draft will almost certainly lack emotional depth. I think this happens as a matter of course as we think about the plot more than the emotional impact of the story. Things like rich metaphor and philosophy of thought and poignant character depth are things for later drafts. Don’t worry they will come as you work through it.

What to do with your first draft?

First, most crucially, don’t show it to just anyone. Don’t send it to competitions, unless the competition specifically calls for rubbish. For the moment, treat it as you might treat a suspect piece of machinery; inspect it yourself, poke at it, ask questions, pull it apart, find the missing pieces, re-design it, re-build it if needs be.

And if you cannot discern your first draft’s “black mechanicals”, take it to a trusted specialist to cast their eye over it and do the same amount of rigorous questioning. That specialist is called a dramaturg.

There is a dramaturg somewhere close by waving their hand at you, smiling. They got nothing but love for your first draft, nothing but love and respect. Their job is to read your first draft and help you see it better so that in turn you will write it better.

Other disasters include:

- becoming discouraged when the first draft bores you to tears.

- giving the draft to someone who smashes the idea and your approach to it.

- writing your first draft and introducing it to the inside of a sock drawer for the rest of eternity.

- dumping out your first draft from your computer because you thought it was an utter dud, only to be inspired later….don’t bin anything.

* Graphic by Georgelazenby

**This quote is often attributed to Hemmingway, who alleged he had written no less than fifty drafts of his wartime love story novel A Farewell To Arms. It’s only a short book. My mind rattles when trying to imagine fifty other versions of it.