“One must never place a loaded rifle on the stage if it isn’t going to go off. It’s wrong to make promises you don’t mean to keep.” —Anton Chekhov, 1860-1904

Good Old Chekhov’s Gun Theory. It mostly works on the principle that everything within a story should be necessary to the telling of it. Gun on stage?—someone gets shot for sure.

This is the second in my blog series of ‘unpack that quote’.

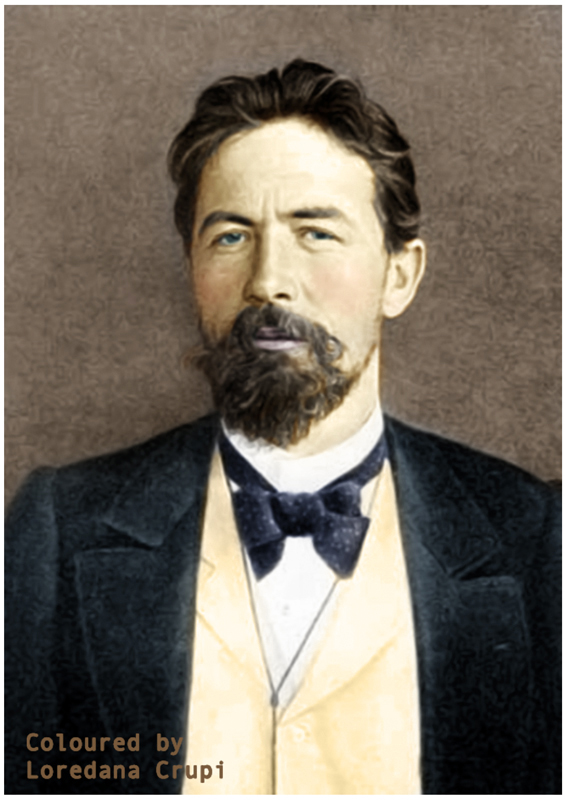

Let’s just get this one thing out of the way first, though, seriously; it needs to be said Anton Chekhov was a hottie. I’d never really paid attention to any photograph of him before. For some reason, I’d always assumed he’d looked like everyone’s dodgy uncle who gets charged up on ‘vodie and Coke’ at family Christmas dinner and spouts inappropriate political rants before passing out on the front lawn.

I was wrong about that. He was gorgeous.

Anton Chekhov, playwright, novelist, hottie and short story writer, took a dim damn view of story clutter. His gun quote appears in various forms in his letters and notes, depending on whether he was referring to the stage or to literature, but the quote is most often interpreted as an admonishment for writers to write only what is necessary for the story to work.

And that’s right. The quote does mean that. In part.

Extraneous matter should be expunged. This not only includes props like guns, but the advice extends to characters, scenes, monologues, events, entrances, exits, subplots, pregnant pauses and…yup, words in general. If it doesn’t need to be there, you have a duty to snip it.

The quote, however, is more than just dear Anton telling you off for rambling writing. It is a far deeper idea. The second half of the quote —the part about making promises— is the real crux. He is talking about audience expectation.

A bloke walks on stage with a gun—just for example. He places the gun on the gun rack. And there it sits, metaphorically loaded with audience expectation. The audience has signed a little contract with you now about that gun—the contract reads something like “I, the author, promise this gun is important otherwise I wouldn’t have shown it to you. We the audience will wait until that gun is put to use.”

Mind you, guns, in particular, naturally offer powerful visual cues on stage or screen, a strong motif of violence and all the attending emotions ( here’s a few; fear, vengefulness, anger, insecurity, bravado, belligerence, vigilance, desperation). However, if an actor carries a vase onto stage, then the emotional implications are less, right? That is, the audience expectations of the use of the vase as a vital plot point are vastly different than that of a gun. So it’s not every little thing that creates a contract necessarily.

But what if the vase turns out important? Perhaps it’s a valuable vase about to be stolen or broken. Or it’s carrying someone’s ashes. Or it’s going to be used as a murder weapon. Ah-hah! See, it’s all relative.

So, the quote is about foreshadowing? It is. But is it as simple as that? It’s not.

For me, the quote actually refers to a broader idea of author promises and audience contracts. It refers to the idea of “set up and pay off”.

The set up and pay off idea runs a little like this; when you set up the anticipation of X by introducing an element of XY early in the story—no matter how subtly or dramatically you do so— you must pay off with an X consequence. This is not to say you shouldn’t surprise your audience or your readers with an unexpected turn of events, but a consequence still needs to be apparent. Failing to deliver a consequence makes you guilty of misleading the audience—you’ve broken the contract. Which is not a big deal at all, unless you wanted to avoid your audience being pissed off with you and staying away from your shows in droves. Like Anton says it’s wrong to do it.

There is a lot to be said about audience expectation.

Just one more gratuitous photo of the lovely Anton. He looks hipster in this one.

And by the way, please avoid putting guns of any kind in your stage/film scripts if you can, even if the gun never does go off, even if you break Chekhov’s rule and no-one is ever shot at, even if you think it’s only a replica of a gun on stage. The reason is quite practical; guns, even replica ones, cost a lot of money and fuss to appear on stages and film sets. I know this is true in Australia, and possibly true in most countries where gun laws strictly control the use and handling of weapons and replica weapons in public areas. With good cause. Firearms have a nasty habit of going off unintentionally. If you seriously need a weapon for the story, think of another one. No, not a crossbow. Jesus. Similar story there.

Wreckless footnote: I’ve also read Chekhov’s gun theory reduced to story tropes. You can read a whole amusing slew of them here.